While developing Eco-Disaster, I came upon a problem.

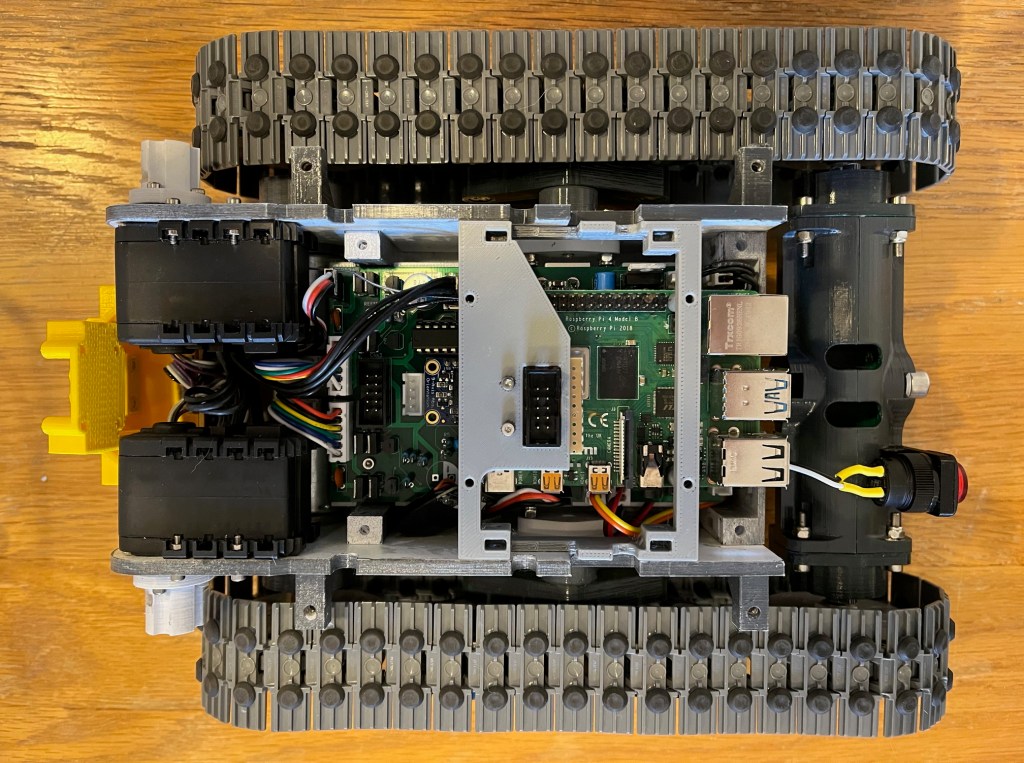

When a barrel has been picked up, the robot heads for the appropriate end zone to deposit it. It uses a core function to drive towards the centre of the largest area of the specified hue until the front time-of-flight (ToF) sensor is triggered by the wall proximity. At this point, the barrel is placed on the floor.

This is what the robot’s camera sees while it’s doing this.

The yellow rectangle shows the extent of the end zone, as calculated by the code. The top of the rectangle is low because the top of the video feed is deliberately cropped so that the robot is not disturbed by things out of the arena. And the two barrels are ignored because they are completely within the end zone: they have been delivered.

To begin with, this works well. But when a few barrels have been delivered you end up with lots of barrels in the centre of the zone. The ToF gets triggered by a barrel rather than the wall and the robot starts delivering the barrels short of the zone. Or it knocks delivered barrels over.

The code now works like this. When looking for the end zone the code sets the top and bottom image crops to a narrow slit. Imagine looking through a letterbox. This is the resulting view:

The yellow rectangle (which is designed to show the extent of the end zone) is now only the height of a barrel. It is also only to the right of the right-most barrel (look closely!); this is because that section of the end zone is the largest block of yellow that the robot can find. The barrels have divided the yellow zone into three, and the right-most one is the largest area. The barrels are now marked; the robot doesn’t see them as within the end zone so they are not considered delivered. The right-most barrel has crosshairs on it because it is closest to the robot centreline; if the robot was looking to collect a barrel, that is the one it would choose.

The robot now drives towards the centre of the biggest blob of the correct hue, just as before. But now it is aiming for the biggest gap between barrels, not the centre of the end zone.